Now that you appreciate the appeal of a whole tobacco leaf fronto roll, check out how this crop came to be where it is today. Did you know that the best tobacco leaves came from Indonesia after the American Civil War?

Only after the US Department of Agriculture began experimenting in Florida with tropical tobacco varieties did W. C. Sturgis, a botanist in Connecticut, become successful in growing Sumatra tobacco from seed and reproducing the thinner leaf in 1899.

The Process Wasn’t Easy

Connecticut farmers used to grow broadleaf tobacco with its easy cultivation process and single harvest, which was most commonly used as filler in cigars. Shade tobacco is much more difficult.

Starting in May, The growing season begins with weeding and transplanting seedlings in long rows. As the plants grow they are attached to guidewires, and then cloth tents are spread over them to increase humidity, protect the young plants from direct sunlight, and maximize the short New England growing season.

direct sunlight, and maximize the short New England growing season.

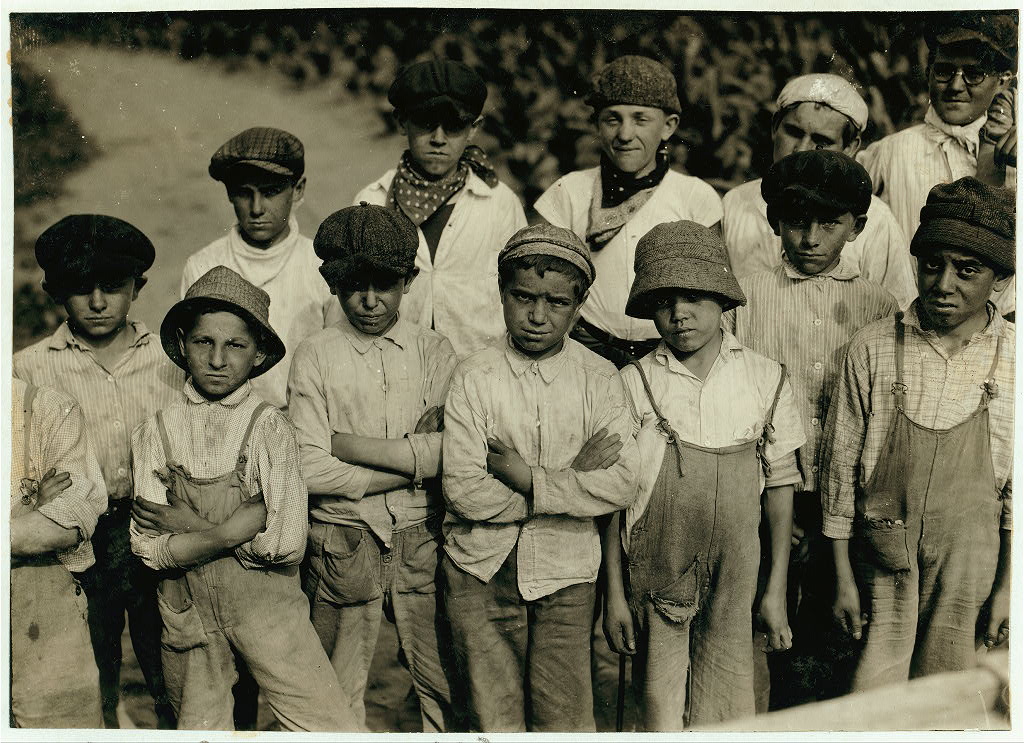

The rest of cultivation takes place by hand. Field workers spend weeks in high humidity and extreme heat moving among the rows, pulling offshoots and tobacco worms. Multiple harvests of leaves are brought to sheds, where workers—most of them female–sew the leaves together to string on a thin strip of wood for hanging, called laths.

Finally, curing the tobacco takes place when the laths are hung up in the rafters of tobacco barns or sheds to cure. After curing, the tobacco is moved to sorting sheds and warehouses, where processing continues throughout the rest of the year.

In order to keep a reliable labor source, the Connecticut farmers cultivated an interesting relationship – with students from the American South, predominantly African Americans.

“For these young people, a summer away from their Southern homes was an opportunity to earn money for their education, enjoy freedom from parents, and get some relief from their segregated existence. Among the thousands of black Southern students who seasonally came north was a young Martin Luther King, Jr.”, writes Dawn Byron Hutchins in her excellent article, Laboring in the Shade.

She continues, “…for black students unable to secure summer jobs in retail or service industries, tobacco was “really the only job opportunity,” according to a group of female students from Plainville. These students, including Anita Baldwin, Taffie Bentley, Norene Robinson, and Gail Williams, responded to flyers distributed at their school in the mid-1950s and were hired to sew in the sheds. The work left them at the end of the day covered in tobacco juice and tar.

Their recollections showed that tobacco was not a summer job of choice:

And it was most embarrassing, so when you got off the bus…we used to run all the way home because we didn’t want anybody to see us …once we got home at 5, it was still an hour to get clean before you could feel comfortable to sit at the kitchen table and eat your dinner.”

Such was the work that went into growing premium quality whole tobacco leaves. Something to think about as you cut and roll your own.

It turns out that many of the students who came north for the summer went on to become prominent and successful individuals, including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Future teachers, doctors, lawyers, religious leaders, and other professionals made up a sampling of former students who had gone north to work in the shade tobacco fields during summers, with some of them returning North permanently.

As noted in this article, “the young Arthur Ashe, Mahalia Jackson, Thurgood Marshall, and Hattie McDaniel were named among the thousands of students who, virtually unnoticed at the time, labored in the shade.”